|

Author: |

Councilor Noemia

Marcelino

Voice instructor at the Brazilian Conservatory

of Music of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Sacred music instructor at the Batista do

Sul do Brasil Theological Seminary

Specialization in piano from the Santa Cecília

de Bauru Conservatory, São Paulo, Brazil |

Welcome

to the MUSICAL IEJU-SA ! |

In this first contact, I’m going to present to you the “do-re-mi” of MUSIC. I don’t know what you think of this subject, but I’d guess you might be imagining that song you heard just now on the radio or television, or someone singing, or that you may be singing yourself. Remember when your mother would sing a lullaby to put your baby brother or sister to sleep?

Yes! All this is music! And it’s much more! It’s your own capacity to make music, meaning to sing or hum a song made up by you or someone else (for instance, pop music composers like Roberto Carlos, U2, the Rolling Stones, Pepino di Capri or Tom Jobim, or operas by the likes of Verdi, Wagner, Villa-Lobos or Carlos Gomes), or to play an instrument (for example, guitar, piano or violin, or even to beat out a simple rhythm on a tabletop), or to appreciate someone else’s playing or singing. All this is music.

When you write a letter or create a poem, you’re using words to record your thoughts and feelings, so as not to forget them at some important future moment, and to let others know your thoughts and sentiments. It’s the same with music: to make it eternal, you need to write down the sounds, rhythms, stops. And to do this, we use special symbols - notes. We call the symbols with which we write music notes.

To write a song we need notes. And to identify the notes, with their names, values, sounds, just like we identify the letters in an alphabet, there’s a place where we can draw them, on a sheet of paper or other smooth surface, or even on a computer screen like yours. This is called a staff.

From : Traçando Letras - Caligrafia B By : Daisy Armuz e Helena de Brito Editora FTD S/A, 2001

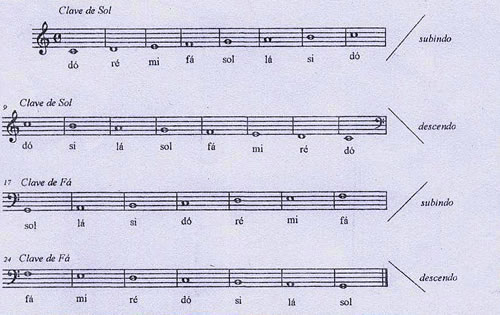

When the CLEF is changed at the start of staff, the names of the notes also change.

The staff is the place

where the music is written, where we place the

notes.

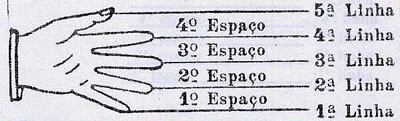

The staff is a group of five parallel horizontal lines spaced at equal distances.

So, just as there is ruled paper to write words, there is ruled paper to write music. The main difference is that each line of music takes up five ruled lines and each one of words only takes one line.

Just as there is a space between one line and the

next to write words, there’s a space between

each line and the next of the staff to write notes,

with one difference: the musical notes are written

in the lines and spaces within the staff. But

there’s another, much larger, space between

one staff (of five lines) and another, where musical

notes are also written.

A space between a musical staff

and another is the same width as one staff, in

the majority of notebooks. But it can and must

be bigger to fit the imaginary suplemental lines,

the writing in two or more voices ,and the letter

of music when sung with human being voice.

Imagine that your hand is a staff

Through your hand you’re entering the wonderful world of music!

How are the notes written in the staff? Like this:

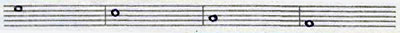

l – In the spaces and on the lines:

2 – Only on the lines:

3 – Only in the spaces:

Musical writing is done from the bottom to top and vice versa, in the direction of an inclined line segment, not horizontal as in alphanumeric writing.

To review: We can write letters, numbers and musical notes on lined paper. But musical notes are written on a series of five lines called a staff, while letters and numbers are written on a single line. Notes are written in a slanted direction, much like the hands of a clock, going (going up or down the lines of the staff) and letters and numbers are written horizontally (in Western languages, from left to right, in Eastern ones from right to left).

There are seven basic notes to represent the sounds that form songs: DO RE MI FA SO LA SI. But more notes are necessary to represent all the sounds that humans can hear. (the sense to hear music is audition; the deaf, although they can’t hear music, have a more refined sense of touch and can feel the vibrations of the notes).

Musical notes are read when written on the staff. But the musical staff only can hold nine notes – four in the intervals and five on the lines. But the number of sounds heard by the human ear is far more than nine. For this reason, to write more notes that represent other sounds, it is necessary to expand the staff, by creating supplementary lines in the spaces above and below each staff. But there are at most only four of these imaginary lines in each space. On a sheet of normal lined writing paper, there is also an imaginary line between the visible ones. On a sheet of calligraphy paper this line is shown, usually as a dotted line. This is how we learn to write in school (as we’ll see), and serves to guide learners in forming letters. After we learn to write, we use this imaginary line automatically and no longer need special paper. In musical writing, it is necessary for some spaces to appear to point them out, at most four, below or above the note, or one cutting the note in half. Unlike horizontal writing, ascending and descending writing, as is

6 musical writing, there is a reference point. This need does not exist in languages that use ideograms in their writing because each ideogram already expresses a complete word or idea – it is already a self-contained set.

A person who has learned how to read music

knows, with this form of writing the sound corresponding

to a note, just by the number of dash marks above

or below this note (in the spaces) and the number

of lines above or below the notes (within the

staff). But for this, it is necessary to have

one more identifying element. Its name is the

CLEF . We’ll learn more about it next class

– but I can say here it’s not hard

to understand and the subject is interesting and

beautiful.

Examples of imaginary lines:

Notes on the upper imaginary lines

Notes on the bottom imaginary lines

Examples:

1. Learn how to write a musical note:

A musical note’s is made of two halves. A note is not a circle.

A musical note’s little ball is more of an ellipse than a circle.

A musical note can be slanted or laying down horizontally, empty or solid, and is formed of two halves, an upper and lower half ellipse, one over the other. It can have a thin stem attached, going upward or downward, as follows:

2. What notes are these? You don’t know? Neither do I. We need to give names to them. How? By placing the staff (the five equally spaced parallel lines) a sign called a CLEF. There isn’t just one CLEF. This is the theme of our next chat.

Note :

If you have any doubts about the above explanation or found it hard going, send me an e-mail through the IEJU-SA site, or a letter to our post office box, explaining your doubt and I’ll answer you directly at the address you indicate. And if you have any suggestions or contributions, I’d be more than happy to receive them and transmit them to our cyber-friends. Maybe we can even have a little chat about music. What do you think?

FINAL COMMENTS

You may not have heard yet, but music uses a field of mathematics called combinatorial analysis. It’s by following these rules that using only seven basic notes our great composers achieve almost infinite variations. And that’s not all. It was a great mathematician of antiquity, Pythagoras, who organized those initial notes according to mathematical calculations

On the other hand, a great French humanist and philosopher was who idealized the from we use today to write music. Before him musical symbols were different. Thanks to his invention, music (in the Occident) can be written, read and disseminated easily, with the help of another great invention, the printing press. And now, with the Internet!

But all this is for other conversations, involving even more stories to tell. I only want to show you here that everything on our planet is interrelated, and sometimes even though these relationships are huge we often don’t perceive the interpretation of concepts of one technological science in another, or even in an art, but these relationships complement each other, and this sensation of plentitude is what leads us to an appreciation of beauty. Mathematics also exercises a huge influence on painting – and the more the painter uses calculations, the more he or she achieves harmony in the finished work. On the corresponding page you’ll find some of these principles.

Bibliography

Curso de Piano , 1st Volume - Mário Mascarenhas. Irmãos Vitale, Ed.

Princípios Básicos da Música para a Juventude , 1st Volume – Maria Luíza de Mattos Priolli, Editora Casa Oliveira de Músicas Ltda.

Traçando letras (caligrafia) – Daisy Asmuz and Helena de Brito – Ed. FTD

Noemia Marcelino

Councilor of IEJU-SA

Author

|